- Home

- Marjorie Warby

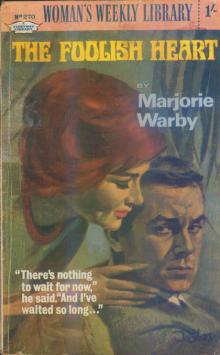

The Foolish Heart

The Foolish Heart Read online

The Foolish Heart

By

Marjorie Warby

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

"The Foolish Heart" by Marjorie Warby,

was originally published by Collins Ltd., London.

Copyright © Marjorie Warby 1950 and 1967.

CHAPTER ONE

The man stood in the doorway, his Alsatian dog at his side, the Kenya sun behind him. His shadow fell across the floor to the girl's feet. Judy Maitland turned, her arm full of canna lilies she had brought from the garden. The scarlet and gold and rhubarb-pink of the flowers glowed like jewels in the amethyst twilight of the shaded room.

"Were you looking for me?" she asked.

"I want to talk to you," said Miles Beresford gravely.

The girl placed her colourful bundle on the round table drawn up near a chintz-covered settee, then she faced the man defensively:

"I suppose you have come to say what Nurse Stevens and the rest of them are saying. That I cannot remain here alone, now my father is dead."

The man walked over the threshold, from the sun-splashed veranda into the large dim room, with its Persian rugs, flung strategically across the polished floor; its comfortable chairs with their floral-patterned covers, the few pieces of good china on the wide stone mantelpiece, and the bowls and vases of flowers perfectly placed.

Judy was an artist with flowers, and spent hours creating floral studies that were both original and beautiful.

Looking about him the man thought what a good job she had made of that room. He remembered it well as it had been in her father's time. The tattered sheepskin hearthrug, chairs with sagging springs and dingy covers. No flowers.

Digby Maitland had let the house go after his wife died, and his little daughter was sent to boarding-school in England. But when Judy eventually rejoined her father on his coffee shamba in the Kenya Highlands, he had given her a free hand to put the place in order, and well she had done it, too. Excellent taste for one so young. Not one false note.

In the empty hearth stood an old copper cauldron which gleamed against the grey stone of the fireplace.

Judy turned her back on the man and, kneeling down, began arranging her cannas in the copper bowl.

Miles Beresford, watching her, thought it tragic that her father, who had spent ten lonely years waiting for his only daughter to grow up, should have met his death so soon after the girl—at long last—rejoined him. He had always been a reckless, dare-devil of a man, and had died a month previously through injuries received in a riding accident. He had left the care of his nineteen-year-old daughter in the hands of his partner, and Miles took that responsibility seriously.

He came close and stood looking down at the shining hair of Digby's daughter, which rivalled the burnished gold of the copper cauldron.

He was a big man, In the early thirties, too rugged of feature to be strictly good-looking, but with, an air of quiet authority that made him a personality not to be overlooked.

Judy, glancing up, found her eyes caught and held by his steady dark ones. She felt at a disadvantage kneeling there, and rose to her feet.

Miles still seemed to tower above her, and something in his glance made her uneasy. He attracted yet repelled her. In spite of the past year, during which they had met daily, she still felt she did not really know him.

He had been her father's best friend as well as partner; a quiet, reserved man, coming up to the bungalow from his own house on the estate, night after night, to play chess with her father, or sometimes simply to lounge well back in one of the deep armchairs and spend the evening smoking and listening to the radio. It was a custom of long standing and sometimes she had felt rather out of it. Her father and Miles had been such pals. Though he had loved her dearly, her father had been inclined to treat her as a child, outside that circle of adult masculine society, and Miles had taken his cue from him.

She would busy herself with the embroidery she did so beautifully, copying the flowers she loved, transferring her own designs to linen, and then painting them with her needle in richly gleaming hues or pastel tints.

Sometimes, absorbed in her task, sitting in the golden pool of light from the standard lamp, she would glance up to catch the steady gaze of Miles Beresford bent upon her. And her heart would give a silly little flutter for no reason at all.

When her eyes met his, he looked away, but sometimes he would smile, the slow, kindly smile that transformed his rugged features and gave his face great charm, and she would be aware of a depth and intimacy in his glance that was never apparent in his manner.

He treated her like a kid, she felt, and that galled Judy, who had travelled out from England alone, and considered herself a woman of the world after her sea voyage.

Miles stood now watching the varying expressions passing across the girl's sensitive face, like cloud shadows flitting over the sunlit plains. He thought, looking at her, that she was not unlike the flowers she held, standing there, slender and straight in her green corduroy slacks, topped by a yellow shirt and the shining banner of her hair. He believed he could have spanned her slim waist with his hands. She looked sweet, and forlorn, and rather fragile, although that air of fragility was misleading, he knew. Judy—as she was fond of declaring—was as strong as a young pony. It was that clear, very white skin that made her look delicate as porcelain.

She grew embarrassed beneath his intent regard.

"Please don't stare at me like that."

He averted his gaze.

"Sorry. I did not realise I was staring."

"Shall we sit down?"

"Thank you. Cigarette?"

"Thanks."

He lit hers and then his own. Judy perched lightly on the arm of the chintz-covered settee. The man lowered his long length into a chair opposite, and Sultan, the Alsatian, flopped at his feet with a gusty sigh.

They smoked in silence for a moment, then Miles leaned forward and said in his slow, deep tones, "I have come to make an offer for your share of the estate. I want to buy you out. I am prepared to be generous."

Judy sprang from the settee, her sea-blue eyes alight.

"Never," she declared. "This house and a half share in the estate belongs to me, and I don't intend to give it up."

"But, my dear child," he said patiently, "be reasonable. You can't live here alone. Not in a country like this. And Nurse Stevens cannot remain for ever."

"I know. I know Stevie will have to go back to Nairobi eventually, but that doesn't mean I need to sell my home. I have another plan. I've been thinking it out, and I do hope you'll agree." She looked across at him earnestly. "Miles, you were Daddy's partner and I want to ask if you'll be mine. Oh…" she added quickly, with a laugh. "How Victorian that sounds! Don't be alarmed, I'm not asking you to marry me."

A sudden gleam shone in his dark eyes.

"But I think that's an excellent suggestion."

"To be partners?"

"To marry you."

She caught her breath, and her face flushed. "You know I didn't mean… this isn't a joking matter."

"I'm not joking," said Miles Beresford.

Judy's heart thumped. Here was a possibility which had not occurred to her, and it held temptation. She wanted passionately to belong somewhere and to someone, to have someone belonging to her. She'd had an insecure background since her mother's death; boarding-school, holiday homes, spells with relations who were kind, but did not welcome an addition to their households.

It had been heavenly to come out to Kenya and her father at last. To be in a house where one had a right to stay. Where one belonge

d. And then Daddy had met with his tragic accident and here she was, back in an unstable world again, to be pushed around by all and sundry.

Miles, mistaking her silence for distaste at his suggestion, said quickly, to relieve what he thought to be her discomfiture :

"It's all right, Judy. Forget it."

She stared at him helplessly. If only he'd say that he loved her, wanted her, convince her that she really meant something to him. But he did not say anything like that. Instead, he observed smoothly: "You wish to go on living on the estate, with me to run the show for the pair of us, is that it?"

"Yes, please, Miles."

"I still don't see how we can share the same house without a licence."

"Licence?"

"Marriage licence. People would talk, you know."

"I am not suggesting that we share the same house."

"Forgive me if I seem dim. You do agree you cannot live here alone?"

"I shan't be alone, I hope. That is the beauty of my plan." Her expressive face lit with animation. "The bungalow will be full of people. You see, I want to run this place as a Guest House. Children welcome. I shall advertise in the local papers. Home-grown produce a speciality. Fresh eggs. Poultry. Strawberries and cream. Oh, Miles, do say you think it is a good idea."

He gazed at her in silence, not fancying the project, picturing hordes of unruly children swarming over his well-kept acres, breaking down the coffee bushes, doing heaven knew what damage.

"This place is a coffee shamba, not a kindergarten," he commented.

"It isn't going to be a kindergarten. Don't be stuffy, Miles, please. I think it's a splendid solution."

"Well, I'm afraid I don't."

"Why not?"

"There will be countless snags. Far better to marry me. Simplify matters all round. It could be a marriage in name only, if you preferred. A marriage of convenience."

"Thank you. I expect you mean well. But when I marry it's going to be for love."

"I see."

They were silent, eyeing one another warily. Then Judy burst out defiantly:

"I won't sell the house, and I don't mean to be turned out. I've been pushed around all my life and I'm not going to be pushed around any more. By you or anybody else. So there."

He stood up then, the expression on his dark face unreadable.

"I see," he said quietly; "If it's like that, then there's no more to be said."

"No," she retorted, "there isn't, is there? I should have preferred your backing, because Daddy thought so highly of your judgment. But if you insist on being an obstructionist, there is nothing left for me to do but carry out my plan in spite of you."

She faced him like a kitten standing up to a bulldog, in an effort to master an absurd desire to fling herself into his arms, bury her face against that broad shoulder and have a good cry.

But he would despise her utterly if she gave way, know her for the child he imagined her to be.

He picked up his hat.

"Perhaps I'd better go before we both say things we might regret…" The huge dog scrambled to its feet at the man's movement. "Good-bye, Judy." He sketched a casual salute, and went by the open door through which he had come. A tall figure striding down the shamba, his dog at his heels.

Judy stood where he had left her, following his departure with her eyes. Her head ached, and she felt very unhappy.

If she had cried, would he have gathered her up in his arms, or would he have remained stiffly aloof until she'd regained control of herself?

Probably the latter. He was an unpredictable creature.

Lydia Stevens sat herself upon the settee and began rummaging in the capacious knitting bag she carried. Her brow was clouded. She felt annoyed that Miles had called and gone again without her seeing him. It was dull enough up here with just the two of them alone in the big silent house. She would have welcomed a little masculine society.

Lydia Stevens was a disappointed woman who owned to twenty-nine, but would never see thirty again. Dark, good-looking, she was capable and ambitious, with a professional veneer of determined brightness that hid a bitter realisation of opportunities missed.

She was not attached to any hospital or nursing home at the moment, but lived in rooms in Nairobi and took cases in private houses, through connections with local doctors. Since the death of Digby Maitland she had remained at the express request of 'Miles Beresford, to keep Judy company until arrangements could be made for the girl's future.

As she had no further assignment for the moment, Nurse Stevens had stayed on quite willingly, laid aside her uniform, and suggested that Judy should call her 'Stevie' as her friends did.

She was intrigued by the situation her patient's death had created. His young daughter and that nice man who had been his partner, now joint owners of the estate. She was interested in Miles Beresford, and felt annoyed with Judy for letting the man go so casually. She began to knit very swiftly, her needles clicking sharply amid soft pink wool.

Judy dragged her mind from her own affairs and focused it upon her companion. Stevie seemed a little put-out, and Judy felt a rush of contrition. She had been selfish, absorbed in her own problems. It must be very dull for poor Stevie…

Impulsively she said, "I'm sorry. Did you want to see him? You are bored here, and no wonder, just we two, day in, day out…" .

"It isn't that. I was thinking of Mr. Beresford. I expect he would have liked to stay—I think he's lonely."

Judy looked incredulous. "Miles Beresford lonely? He's the most self-sufficient man I know!"

Stevie went on knitting.

"You are not the only person who grieves for your father," she said quietly.

Judy flushed, feeling herself reproved. She said defensively:

"Miles doesn't inspire sympathy. He is such a poker face. Impossible to know what he is feeling or thinking."

"He has been most considerate for our welfare since I came. It might be a nice gesture to ask him along for a meal, don't you think? I understand he was a constant visitor during your father's lifetime, but maybe he hardly likes to drift in now without a proper invitation."

"I haven't felt like entertaining," muttered Judy, a lump gathering in her throat.

"Of course you haven't!" Stevie, by a deliberate effort, softened her tone; "but you must pull yourself together and face the future soon, my dear. You'll feel better when you leave this place, it is too full of reminders."

"You don't understand. I wouldn't leave here for anything. This is my home. The only real home I've ever had. I lived here as a small child until my mother died, and then I was sent to school in England. But I've no roots there. No-one to whom I could go."

"But you cannot live here alone," objected Stevie, trotting out the usual arguments. "It isn't safe in this country."

Judy withdrew her gaze from the blue distance beyond the veranda and fixed them upon her companion sitting taut and trim in a maize linen frock, busy fingers at work amid pink wood. An overwhelming desire to confide in someone possessed Judy.

"Miles has a solution for that problem," she told Stevie. "He asked me to marry him."

The pink knitting dropped into the yellow lap. "And are you going to?"

"No," said Judy; "at least, I don't think so. You see, when I marry I want to marry for love. He didn't say anything about being fond of me… As proposals go"— she tried to make a joke of it—"the whole thing was rather a wash-out!"

Lydia Stevens sat silent, digesting Judy's unwelcome information. She had hoped Miles Beresford was becoming aware of herself. It was always the same these days. Whenever she met a man she liked, he invariably proved to be tied up with someone else.

She was too mature to interest, or be interested in, the majority of young bachelors she met, and the older men were invariably already married. It was this realisation that was causing a panicky sensation beneath her facade of cheery self-confidence. Stevie wanted to be married, and feared she had waited too long.

Meeting M

iles had caused her fading hopes to soar. Someone her own age, and an eligible bachelor. Attractive, prosperous, and lonely. And now this bombshell. He had asked Judy to marry him.

Understandable, of course. The girl had charm.

"I can't help wondering why he asked me," Judy went on as the silence lengthened.

An idea sprang into Stevie's mind on the instant. A reason she had no difficulty in persuading herself must be true.

"The property, of course," she said. "The property?"

"I don't mean to be unflattering, dear. But I think there can be no doubt about what he's after. Miles Beresford wants the estate. All of it; not just a share."

"Oh!" cried Judy, stricken by the suggestion. "Not for that… surely?"

"Why not? He's a good farmer, and a shrewd business man. It must be galling, don't you think, not to own the place outright?"

"But…" began Judy, hating this proof that Miles's offer had an ulterior motive… "I don't think he'd do a thing like that;" she stopped short. She heard again his pleasant voice in her ears: 'I have come to make an offer for your share of the estate. I want to buy you out…' He had not asked her to marry him until she had refused to sell. It must be true, then.

He was ready to marry her in order to gain complete control of the land. How humiliating. And she had been trying to persuade herself he cared.

"Well, it doesn't matter really. His reasons, I mean," she said then, in a crisp voice from which all trace of wistfulness had departed. "I have another project and marriage doesn't come into it." Then she proceeded to unfold to Stevie her plan about running the bungalow as a Guest House.

Lydia Stevens put down her knitting and listened attentively.

Judy could scarcely run such a place single-handed. Would it be worth while to suggest staying on to help? Many a good husband had been caught on the rebound— just supposing Miles Beresford really was fond of this girl— and Stevie had no qualms about being second best. She was past being choosey now. She leaned forward, veiling her eagerness. "You couldn't run a Guest House alone though, could you?"

The Foolish Heart

The Foolish Heart